Cornish Artists and Authors at War (1914-1919)

My research into the St Ives, Newlyn, Lamorna and Polperro art colonies, as well as in connection with my biographies of the submarine commander, George Bradshaw and the cavalryman, Crosbie Garstin, has led me to come across paintings and descriptions of a vast range of First World War experiences. Pulling this altogether into a subject for a special feature (and a lecture) has proved immensely rewarding and the story so told gives a fascinating multi-focused view of this horrendous conflict. One's emotions get twisted this way and that as one hears of the initial enthusiasm and the unbridled patriotism of the recruits, their resilience amidst quite appalling circumstances, their boredom, only enlivened by such humour as they could find in their predicaments, and then the terror and the valour and the horror when called into often futile action. There are plenty of stories of infantrymen from the Western Front, but there are also tales of the Cavalry and the Machine Gun Corps, there are tales of Ireland at the time of the Easter Rising, of Russia at the time of the Russian Revolution, of Belgian refugees, of the submarine service, named 'the Suicide Club'. Then, there is the position of foreign artists - some were driven out by Cornish jingo-ists, others, to the admiration of their peers, enlisted voluntarily. Cecily Sidgwick, of German origin and known for her German characters in her romances, responded by including ever-grosser caricatures of the Hun in her novels. There were commissions from the Canadians for Alfred Munnings and Laura and Harold Knight, but Harold Knight's pacifism attracted particular opprobium in 1918. However, Ernest Procter, another conscientious objector,did useful work with the Friends' Ambulance Unit. To lighten up the mood, Crosbie Garstin produced for 'Punch' hilarious accounts of life on the front line to counter balance the true story told in his letters. This is a story, by turn, uplifting, heart-rending, horrifying, funny and sad, with much fine art to admire.

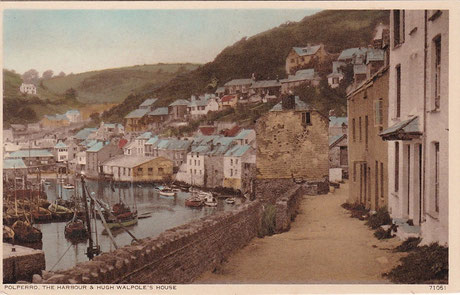

The impact of the Declaration of War at Polperro

The novelist, Hugh Walpole, had a cottage, 'The Cobbles', on The Warren, Polperro, from 1912-1921. Aware that momentous events were about to unfold, he began a war diary on 29th July 1914, which he later published in 1934. His entry for 30th July included the section, “Still an atmosphere of humorous indulgence - no one taking it really seriously. All of us convinced that nothing actually happens - and Englishmen always come out on top.” Then, on Sunday 2nd August, the men in the Naval Reserve were called up. “Get up to find whole village in a ferment - women crying, men cheering. First detachment go at 9.30 a.m.”

This period also featured in Arthur Quiller-Couch's novel, Nicky-Nan, Reservist (1915). This recorded how the fishing had recently been poor and, with the War starting in early August, all hopes for the pilchard season were dashed, for most of the men were Royal Navy reservists, which meant that they were called up, “in a stupor”, straightaway. Their gun practice sessions off the coast were the final straw, sending the pilchards down into the deeps. The children used the news to invent new games, so that the boys played ‘English and Germans’ - the weaker boys being coerced into representing the Teutonic cause and afterwards joining in the cheers when it was vanquished. The following day, the boys had a naval enactment in row boats in the harbour, which they enjoyed far more, as half of them intended to join the Navy, having seen the speed trials off the Polperro coast.

Quiller-Couch was later vocal that too many local men were joining the dockyards at Plymouth rather than enlisting.

War News in St Ives

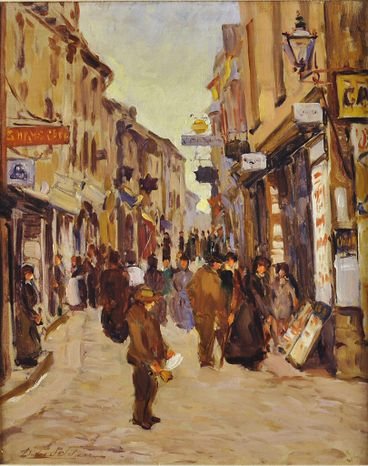

Dixie Selden was an artist from Cincinnati, who came to St Ives in the summer of 1914 to join the Summer Art Class run by fellow American, Henry Bayley Snell, the head of the Philadelphia School of Design for Women. Her painting shows the Town Crier drawing the attention of people in Fore Street, St Ives to the posting of new regulations and news. Irma Kohn, another American student in the class, in an interview when back home, commented,

“It was on the Wednesday that the news came that England had declared war and Sunday, the fishermen, who were among the first to go, bade farewell to their families and were taken to London for mobilisation. It was apparent that the fisher folk were much depressed and fearful. St Ives is a great coaling port and the unloading of the huge barges of coal was delayed on account of the scarcity of men. People surrounded the billboards of the town, where the news of the war is bulletined, all day long, in eager anxiety for news from the front.”

The editor of The Cornishman commented,

“We have had no actual experience of any war of a serious kind in this country since the time of Cromwell, and we hardly yet realise how entirely we are in the hands of the war authorities. They can without any civil proceedings or ceremony enter any house by force, order the lights to be put out, require all persons within any area to remain indoors between stated hours. They have the power to take possession of any land, building or moveable property they like. They can demolish your house, arrest you without any warrant, order whole communities to leave specified districts and close public houses. All this far from exhausts the powers now in the hands of the naval and military authorities. It sounds a little strange to us in this fair land of liberty and freedom, but happily we all know that wisdom and discretion will govern the operation of these martial regulations. War is a ruthless business, and all private considerations have to give way before the necessities of the State.”

The famous New Zealand artist, Frances Hodgkins, came to St Ives on the outbreak of War, having been displaced from France. She later called her St Ives period her 'experimental years' and she owed a huge debt to the financial and emotional support of Moffat Lindner.

As a result of Lindner’s wife's proactive approach, St Ives was the first town in Cornwall to welcome a group of Belgian refugees and Hodgkins did a number of paintings of the Belgian families (see also Auckland's Refugee Children). It is considered that this painting was exhibited for the first time as Unshatterable at the International Society’s Autumn Exhibition in 1916, but, if so, it seems an odd title, as only the baby appears oblivious to trouble. The nursing mother seems devoid of expression, and the older children are tense with anxiety or fear. Behind this group, a gap in the swirling grey suggests the fact of the missing father, lost in the symbolic clouds of war. Within the wall of monochrome, intense colour is reserved for mother and child - and, as the death toll continued to increase, Hodgkins was to feature this relationship more and more, as the rebuilding of civilisation was dependent on it.

Joey Carter Wood was the brother of Florence Carter Wood, who was Alfred Munnnings' first wife, and was a regular visitor to the Lamorna art colony. Accordingly, he features heavily in Jonathan Smith's novel, Summer in February, but his characterisation in that novel does not appear to be based on substantive fact. Joey, whilst a nature lover, was actually a diligent artist, who was hung a number of times at the RA and at Liverpool. He was also 'handsome, talented and charming', and will have been devastated by his sister's suicide in July 1914.

After War broke out, he soon volunteered his services and joined the Coldstream Guards. He was gazetted a Second Lieutenant on 9th October 1914 and initially served with the 4th (Reserve) Battalion at Windsor. On 22nd January 1915, he was posted to the 2nd Battalion on the Western Front, where he acted as a platoon commander in the 4th Guards Brigade. On 30th January, his Brigade marched to the vicinity of Bethune and took over late that evening trenches at Cuinchy on the right of the British line. On Monday 1st February, the Germans attacked early in the morning, initially overpowering one of the Brigade’s trenches, and, in the subsequent counter-attacks, which were ultimately successful, Joey, and Captain Lord Northland, were the two officers, amongst the twenty-two members of the Brigade, to lose their lives. Fifty two others were wounded. Joey’s time at the front line lasted just ten days. He was the first Cornish artist to make the supreme sacrifice.

He is buried in Cuinchy Communal Cemetery, Loos, France (11.B.27), and is commemorated on the Upland House School memorial in St Martin’s Church, Epsom, and on the Christ Church, Silloth, war memorial.

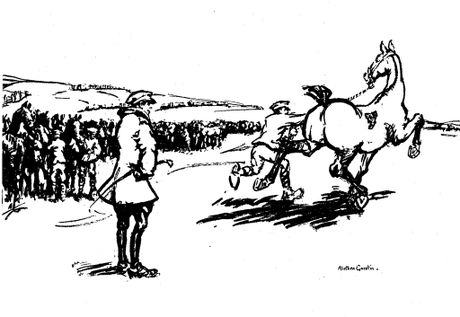

Crosbie Garstin, who became a well-regarded author, was the eldest son of the Newlyn School painter, Norman Garstin, and had been working as a cattle ranch manager in Bechuanaland, when War broke out. Accordingly, when he returned to England, he enlisted in a colonial cavalry regiment, King Edward's Horse. Having trained at Watford and Bishop's Stortford, he described in an unpublished piece called 'Getting There' his trip to the front, leaving from Bishops Stortford at dawn. Below are a few small extracts.

Extracts from Getting There - original at Cornwall Records Office.

“We were off at last, off to the real thing, off to France; “battle, murder and sudden death”. The column wound down the hill, over the downs into the town, and clattered through the sleeping streets. A lone policeman, standing in the shadow of the Town Hall, saluted, and was cheered heartily. We cheered the swinging sign-boards of our hostelries, the Black Bull, the King’s Head and the Three Feathers; we’d drink their tap-rooms dry when we came back from Berlin, we shouted. A cat, that slipped across the street before the advancing hooves, came in for its round of applause...... Dawn was breaking pearly in the east when the last horse was entrained. The engine whistled, the station master and porters waved their caps. With cheering heads jammed through every window, the train pulled slowly off the siding, as the first sun ray set the church vane twinkling. We rumbled through the suburbs of London, blinking awake to its workaday, everyday round. A few half-dressed women at back windows kissed their hands to us, and a baby waved a penny Union Jack.”

Having arrived at Le Havre, they eventually received orders to ride out of town to a Rest Camp (no 6) for the night.

“Signs and tokens of the British were everywhere. British transport wagons rattled over the cobbles in every direction; British staff-motors purred past, vanishing toward every point of the compass. At every cross-road stood a supplementary signpost painted in English. On the windy plain above the town, we came to the Rest Camp, a city of tents, ordered into streets and squares that spreads over the upland like a field of giant mushrooms.”

Late the following day, they rode back into Le Havre and boarded a draughty, uncomfortable train, sleeping on straw on the floor, heads pillowed on haversacks. At dawn, they halted at a country station to water and feed the horses. For the rest of the day, the train rumbled north.

“At every bridge, an ancient French territorial, in a makeshift uniform, stood beside his straw sentry-box and brought his antiquated musket to the shoulder. At every station, the buffet women came forward, offering bottles of country wine, bread and chocolate for sale.”

When a train passed, loaded with French troops, Garstin’s comrades all cheered heartily, and another cheer rang out as they spotted a troop of Indian cavalry halted at a level crossing. However, they then came across a more thought-provoking sight.

“A British ambulance train lay on the siding, even then taking aboard its freight. I got an impression of gleaming white enamelled interiors, tiers of cots and bustling orderlies. A tall nurse stood at one door, the cross of her order scarlet on her breast, directing the orderlies as they lifted the loaded stretchers aboard. She gave us one instantaneous glance of her calm grey eyes, then dropped them again to her work. We were now material for the Machine; she was concerned only with the broken parts. All along the trackside lay the stretchers, a quiet man, covered with a brown blanket, on each. Some had their faces turned away, some lay over on their faces, one had his forearm thrown across his eyes to protect them from the setting sun. They all lay perfectly still, and not one made a sound.

Our fellows had stopped cheering; we had seen the other side of the picture, the real one and we were getting very near ourselves......."

"Faintly, then distinctly, from the north came a sound that thrilled me to the core - the bump, bump, bump of heavy guns....We mounted and rode away down a poplar-lined road, straight towards the booming hills. The bump, bump of the big guns increased and fused into an almost continuous thudding. Now and again, there was a flash on the ridge as if someone was striking and blowing out matches - shell bursts. The star-shells curved against the sky and fell trailing sparks, like tired shooting stars. From time to time, the faint staccato chatter of rifle and machine gun fire drifted down wind. This was IT! the Line! the line on which the fate of Europe hung and the eyes of the world were turned.

Our men, men who had gone before us, singing and cheering out of England, were out there on the black ridge among the thunder and lightnings, holding on. We rode forward, thrilling.”

Crosbie Garstin - A Blinded Mole

The reality of War soon hit home and cavalrymen like Crosbie became very frustrated that they rarely had a chance to act as a mounted mobile force, for the new, modern way of waging war meant that there were always severe obstacles to their effectiveness. Not only did horse and man together present a much bigger target, it not mattering over much which one was hit, but their ability to operate at speed, their greatest asset, was continually hampered by the terrain, which, if not a sea of mud, was filled with grids of trenches, rolls of barbed wire, trip-wires, and numerous shell-holes, in which horses could easily break their legs. On the few occasions when they were sent into action on horseback, they often suffered appalling losses. Accordingly, in the early part of the War, they tended to perform logistical roles as ‘hewers of wood and drawers of water’ to the Infantry. They also got involved, inter alia, with the construction of defence posts, the repair by night of trenches, the furnishing of a few observation posts and as guards of prisoners. Crosbie indicated his frustration in his poem, The Trooper, written in Artois in 1915, from which the following is an extract.

“Now here I am like a blinded mole -

Toil in a furrow and sleep up a hole -

Dug in a grave twelve foot by three,

My strappings bust and my spurs all rust,

With nothin’ but two mud walls to see,

Sluiced with the drivin’ sleet:

Me! that was in the Cavalry,

The saucy, swaggerin’ Cavalry.

Sloggin’ my two flat feet!

I longs all day and I dreams all night

Of a slap-bang, Tally-ho open fight;

One fair chance on the open plain,

Then knee to knee like a wave of the sea

We’ll blood our irons again and again

In thunderin’ squadron-line......”

Denis Garstin - Into Action

Denis Garstin was Crosbie's younger brother and also had literary aspirations, having been Editor of The Granta, the Cambridge University magazine. Having gained a commission as a member of the Cambridge O.T.C., Denis had no difficulty in successfully applying for military service. He enlisted on 31st August 1914, and, following training, he embarked for France on 18th May 1915, joining his regiment, the 10th Hussars, as an officer in the machine-gun squadron.

Into Action, Denis’ account of his journey to the Front, which was published posthumously in The Shilling Soldiers, matched that of Crosbie in many respects. There was the same unbridled enthusiasm amongst his colleagues, with constant cheering and singing, and all were confident of an early victory. They arrived in France at Le Havre and then stopped en route in a bustling Rouen. “Most of us felt angry that we had been kept back in England all these months and were only now going in, after our friends had borne the brunt.” When they got to Hazebrouck, they heard a sound like breakers booming on a shore - but it was guns. When someone asked if they were ‘our guns’, the subaltern snorted, “My dear old thing, didn’t you know we haven’t any?” and then went on to say that "the regiment had been badly smashed a few days earlier and that directly we had been reformed, we’d probably go up again and be smashed again. And so on...We haven’t got a damned thing, not even men.” (p.15). Even this stark analysis did not puncture the new arrivals’ confidence - the subaltern was merely put down as a pessimist. However, the reality soon sunk in. Despite being cavalrymen, they were now expected to man the trenches. On their way to the Front, they passed through Ypres, in total ruins and still burning. “On either side, the houses roared and crackled and came crashing down, as a great tide of flame surged through the shattered buildings, now sending out deep waves of fire, now a foam of sparks. Against the dark sky, the city was incredibly bright, for every ruined facade that was not itself burning reflected the glare of its blazing vis-a-vis; and the long column of troops, marching it seemed into the very flames, looked strange and fantastic in the leaping blaze... Beyond the city was desolation, a wide dark plain cut with shallow trenches and shell-holes, encumbered with endless wires, and littered with broken carts, dead horses, rifles, kit and odd remnants of old cottages long since destroyed.” (p.15-6)

Having taken up his position in trenches by Sanctuary Wood, Denis realized the enormity of the task facing them. Here he had to hold the line at all costs, with no troops and only one battery of field guns behind them, with only twelve shells a day. Soon, they were subjected to a huge bombardment, expecting any moment to be attacked from all sides with the Germans having broken through the lines, but, somehow, it did not happen.

In addition to this involvement in the Second Battle of Ypres, Denis went on to fight in the Battles of Albert, Loos and Thiepval Ridge. The stories in The Shilling Soldiers are much more horrific than anything Crosbie produced. They do not shy away from portraying in intricate detail the carnage and the futility of the actions. Denis is open about his fears, and dreads revealing his inner turmoil to his men. ‘I remember wondering why the devil I was there, and why on earth a lot of utter strangers would come running across the badly beaten ground and bayonet me. It seemed so stupid’. He describes men's reactions when they knew they were going to die, and several men, often those considered the hardest types, going mad and charging at the enemy to put an end to their suffering. He also often indicates that no-one really knew what was going on and he describes how seeming victory at the Battle of Loos turned into a dishevelled retreat. The stories capture the horror, as thousands of men die around him, and demonstrate how all ranks tried to cope in the mayhem. There are some touching moments, and some humour was needed to get by.

In the final story, Vale, Garstin's C.O., who is convinced he will not survive, urges Denis to take on board how the officers and men have worked together and consequently admire and respect each other, how this was an ideal that should be able to be applied to business and the social system. If the officer class had the confidence to apply this ideal on returning home, then perhaps the class wars of old could be avoided.

Hugh Walpole in Russia

Whilst poor eyesight meant that Walpole was not able to enlist, he was very keen to 'do his bit'. Having also been rejected by the Cornish police, he was offered, in late August 1914, a journalistic appointment based in Moscow, reporting for The Saturday Review and The Daily Mail, which he accepted with alacrity.

Whilst in Moscow, Walpole managed to get himself appointed as a Russian officer in the Sanitar, which, as he told Henry James, was “the part of the Red Cross that does the rough work at the front, carrying men out of the trenches, helping at the base hospitals in every sort of way, doing every kind of rough job. They are an absolutely official body and I shall be one of the few (half-dozen) Englishmen in the world wearing Russian uniform.” In the summer of 1915, he worked on the Austrian-Russian front, assisting at operations in field hospitals and retrieving the dead and wounded from the battlefield. In another letter home to a literary friend, he told Arnold Bennett, “A battle is an amazing mixture of hell and a family picnic – not as frightening as the dentist, but absorbing, sometimes thrilling like football, sometimes dull like church, and sometimes simply physically sickening like bad fish. Burying dead afterwards is worst of all.” During an engagement early in June 1915, Walpole single-handedly rescued a wounded soldier. As his Russian colleagues refused to help, Walpole carried one end of a stretcher and dragged the man to safety. For this, he was awarded the Cross of Saint George.

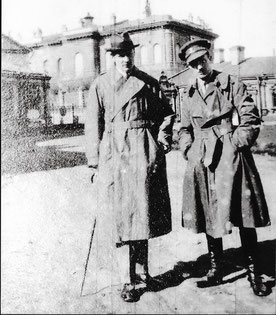

After this tour of duty, Walpole returned to Petrograd, and then, in October 1915, came back to England. In February 1916, he was asked by the British ambassador in Petrograd, Sir George Buchanan, to take charge of a new Anglo-Russian Propaganda Bureau to counter Germany’s highly effective propaganda. Here he linked up with Denis Garstin (see below). He witnessed the Russian Revolution in February 1917, but this rendered his role redundant and he left just before the Bolshevik Revolution that November. Back in England, he continued to work in British propaganda for the Ministry of Information under Lord Beaverbrook.

Swedish artist flung into prison on trumped-up charge

Rolf Jonnsen was a Swedish artist, who, whilst studying at the Forbes School in Newlyn, married a local girl and settled in the village. He had been there for a couple of years prior to the War. However, someone accused him of signalling with coloured lights to the enemy and he was thrown into prison at Pendennis Castle. It took some months before he was tried, when it emerged that all he had been doing was walking with a torch from one room in his house with one colour curtains into another room with different coloured curtains! Such jingoism had been stirred up by the media who contended that the county was swarming with spies.

The story of the Austrian, Count Larisch, in St Ives and of D.H.Lawrence and his German wife, Frieda, at Zennor are other examples.

New Zealand artist dies on Home Defence duties

Herbert Babbage was a New Zealand marine painter, who had been a regular visitor to St Ives since 1905. However, he felt sufficiently patriotic for the mother country to enlist as a private in the 4th Duke of Cornwall Light Infantry for home defence duties, and his unit was posted to Wales to guard railway facilities used for the distribution of coal. However, he died in Cardiff Hospital in October 1916, following what was described in his obituary in the local paper as a short illness and an operation, but one account of his death indicates that it was caused by exposure whilst on sentry duty. A close friend, probably Edith Skinner, published anonymously a poem in his memory in the local paper, highlighting his love of Cornwall - see below. He is one of four names recorded on the WWI memorial plaque in the St Ives Arts Club.

The Spring will come and carpet wind-swept Clodgy,

With those dear flowers, you always found so fair,

Rich golden gorse, sea-pink, the sweet pale primrose,

Deep orange lichen on the grim rocks bare,

And I shall grieve because you may not see them,

Not know that they are there,

In God’s own Heaven, there blossom flowers more rare.

When the lark rises in the dews of morning,

And tries at Heaven’s gates, his song to sing,

I shall remember how you loved to hear him,

And watch his fluttering wing,

And I shall grieve to think that nevermore,

May you hear any-thing,

In God’s own Heaven the angels sing.

When the sea foams in wild majestic grandeur,

Covering dark rocks with snowy wind-lashed spray,

Or, gently murmuring, washes with soft caresses,

The golden-sanded bay,

My heart will ache because you may not see

The glory of the day,

In God’s own Heaven, there is a Golden Way.

My friend, who with no thought of ought but duty,

Left all you loved to answer England’s call,

Giving up ease and liberty and comfort,

To fight against odds, your back set to the wall,

When I remember all you have suffered,

My tears will fall

In God’s own Heaven sits one who gave his life for all!

Artist colleagues honour over-age American artist who decides to enlist

Elmer Schofield was an American artist, who married an English girl, who hated America. Thus, he spent roughly six months of the year in England and six in America, where he was considered one of the leading American Impressionists. From 1903-7, his family was based in St Ives and he was thereafter a regular visitor to Cornwall, working in Polperro in 1912-3.

In 1915, despite being an American citizen and aged 48, Schofield felt sufficiently deeply about Germany’s actions that he enlisted as a private soldier in the Royal Fusiliers. Two addresses presented to him at a dinner held in his honour in September 1915 (see below) show the huge respect for his actions afforded him by the St Ives artistic community. With the assistance of Julius Olsson, who was horrified that he had enlisted as a private, he received a commission from the Royal Artillery the following year. He fought at the Somme and rose to the rank of Major but his only painting exploits were in camouflaging the guns under his command. In a letter home, he commented, “Isn’t it strange! A peaceful man if ever there was one and here I am rucking about in the middle of a terrific battle and rather enjoying things.”

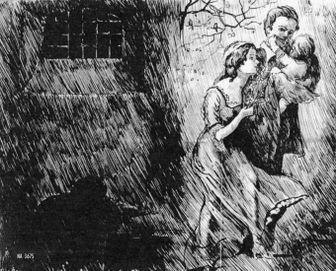

Herbert Butler's The Homecoming

Herbert Butler first painted in Polperro in 1884 and settled there with his wife, a Polperro girl, in 1900. He was then resident there until his death in 1931. This painting shows a soldier, modelled by local boy, Bertram Puckey, at home on leave. His mother and sister are the ones most concerned about his well-being and interested in his stories. One imagines that the brother at the back, who has clearly demonstrated that he is a good shot, is rather worried that he will be cajoled into enlisting himself.

Crosbie Garstin, in a series of stories, gave hilarious accounts of the conflicting emotions of those going home on leave.

Large collection of impressive War sketches

in Imperial War Museum and Plymouth Art Gallery

Robert Borlase Smart was brought up in Plymouth but, from 1911-1914, had studied marine painting under Julius Olsson in St Ives. After the War, he settled in St Ives and was to become one of the most important figures in the history of St Ives art.

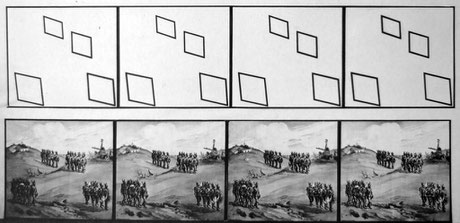

Smart enlisted in the Territorial Force in January 1915 and, by June, had become a Sergeant. He then joined the Artists’ Rifles Officer Training Corps and was made a Second Lieutenant at the end of July. After the Artists’ Rifles were subsumed into the 24th Division of the London Regiment that autumn, he was seconded to the Machine Gun Corps. In January 1916, he was promoted to Temporary Lieutenant, and he served on the Western Front between June and September 1916, arriving immediately before the Somme Offensive and witnessing its after effects. He also witnessed the first tanks in action and their deficiencies. However, rather than go with his Division of the London Regiment to Salonica in November 1916, Smart stayed on at the Machine Gun Corps’ Training Centre at Grantham. Given both his teaching and art qualifications, Smart found his niche as an instructor at Grantham, specializing in “instruction diagrams for cavalry, infantry and machine gun training” and in camouflage. He was 2 i/c to Edward Handley Read.

From sketches done during his time in France, Smart produced a series of 18" x 24" charcoal and watercolour drawings of scenes that he witnessed from Vimy Ridge to the Somme. As no war artists had been appointed at this juncture, his depictions of the after-effects of the battle of the Somme are of great interest and importance. The Somme Offensive, as seen from the Madagascar Dump, Arras Road, in the Imperial War Museum collection, is typical of the wastelands he depicts, with shell-shattered trees, roads converted into muddy quagmires, with fierce fighting as a backdrop.

Smart held exhibitions of his drawings in Plymouth and at the Fine Art Society in 1917-8, with the Imperial War Museum buying seven works - seven of the first ten works it ever acquired. It now has 32 works by him and Plymouth Art Gallery has 14. See list

Below are some black and white prints from the family's collection, albeit the originals were all brightly coloured. Grandmother is also in the Imperial War Museum collection.

One of the projects that Smart worked upon was the design of wooden structures, which were laid flat on the ground, but which, when pulled upright, looked like fighting men. These were used to make the Germans believe that a night attack was being launched at this spot, whereas the true point of attack was very different. The image on the right shows how the ploy worked.

One of Smart's images depicted a sight that soldiers at the Front all remembered - the ‘Leaning Virgin’ of Albert, for the town was just three miles from the front lines. This was the name given to the statue of Mary and the infant Jesus, designed by sculptor Albert Roze, on top of the Basilica of Notre-Dame de Brebières in Albert, after it was hit by a shell on 15th January 1915, and put into a precarious horizontal position. The Germans said that whoever made the statue fall would lose the war, and a number of legends surrounding the ‘Leaning Virgin’ developed among German, French, and British soldiers. In the end, after the Germans had recaptured the town in March 1918, the British, to prevent the Germans from using the church tower as an observation post, directed their bombardment against the Basilica, destroying the statue. Both the Basilica and statue have since been rebuilt.

Crosbie Garstin and the Easter Rising 1916

Having been commissioned a Second Lieutenant in September 1915, Crosbie was posted to Ireland to act as Riding Master to the Reserve Squadron of King Edward's Horse. His training role, however, was eclipsed by the outbreak of the Easter Rising in Dublin on 24th April 1916. This was an attempt by a group of Irish Republicans to take advantage of Britain’s involvement in the War with Germany to overthrow, with German assistance, British rule. However, it was not well organised, and the interception of the German U-boat, carrying arms to help the rebels, immediately prior to the date set for the Rising, meant that, outside Dublin, few of the planned insurrections occurred. Nevertheless, at the time, it was extremely nerve-wracking. Crosbie described the situation as “like living on a powder magazine”. “Everybody got the jumps, wired, phoned and wrote for help - “going to be attacked tonight, tomorrow, the day after - send help”.” This was particularly the case as Longford, where Crosbie was based was the seat of a Catholic Bishop, and a hotbed of Sinn Fein sympathizers, whilst the Reserve Squadron were the only troops available in the area between Dublin, seventy miles away, and the coast.

With communications down with Dublin and The Curragh, the Commanding Officer, Major James, took it upon himself to take control and issue proclamations banning travel to Dublin without a pass, impounding cars and petrol and imposing a curfew. Despite being short of rifles, ammunition and horses, he also sent out “intimidatory patrols”. Crosbie was impressed, “Wherever we anticipated trouble, we sent out a force that got there first and the trouble failed to materialize.”

Crosbie, who was made an Intelligence Officer with immediate effect, was first sent to Mullingar, twenty-eight miles away, where there should have been a garrison, but where the barracks were empty. However, due to lack of horses, Garstin and his four men had to use bikes, and as Crosbie had not ridden a bike for years and it was “a stiff push against the wind”, he did not enjoy the experience at all. Furthermore, he indicated that “it was a jumpy trip because nobody knew what would happen along the road”. Garstin’s arrival at Mullingar was considered by the civil authorities there most opportune, as they had convinced themselves “they would be murdered in their beds”. He was next sent to Roscommon, where a patrol of fifteen mounted men had been sent three days earlier, when it was thought that eight hundred rebels from Sligo were poised to attack. Crosbie took the view that “most of it was scare” and, as the regiment could not spare such numbers, he withdrew the patrol. He next went to Granard, from where the District Inspector had wired in the middle of the night, indicating that a group of one hundred armed Sinn Feiners from County Cavan were intending to disrupt the bi-annual fair being held the next day. Accordingly, Crosbie set off at 5 a.m. with eighteen men and an officer. They found the town full of roughs, “but they straightened up when we rode in”, and the Cavan rebels, having got wind of their arrival, thought better of it. Crosbie got back to Longford at 8 p.m. that night, and was sent out at 10 p.m. in a motor to fetch in arms from the West Meath border. It was a strenuous time and he commented, “The men have hardly had their boots or bandoliers off all the time and the horses have travelled the limit.” He also indicated that “the O.C. is pretty pleased with me.”

As Major James had also arranged for all mail to be censored, accounts written by Longford men to their families of their part in the Rising helped to seal their fate, when it petered out after a week. Crosbie was detailed to take a number of Sinn Feiners down to Dublin to be tried. He was horrified by what he saw there, “Sackville Street is in ruins, many of the great buildings nothing but a heap of smouldering debris. The big P.O. just a hollow shell of a building; Liberty Hall shelled to the ground etc etc and so on.” As regards the rebels being tried for their involvement in the Rising and in the looting which accompanied it, he commented,

“I never saw such a miserable crowd in my life, looked like a bunch of pickpockets, miserable stinking degenerate lot...They are a rotten bunch, they looted wholesale, fired buildings and shot at almost any darn thing they saw, civilians and all - shot ‘em with lead elephant bullets, buckshot and other foul stuff we would shoot one of our own men for using on the Germans.” No doubt a number of people will take issue with such a description but that is what he wrote.

Wounded and Discharged Lamorna Artists

The Lamorna artists,

Frank Gascoigne Heath (research courtesy Hugh Bedford), Richard Weatherby (research courtesy David Bradfield) and Algernon Newton (research courtesy James Whitaker),

all enlisted but were subsequently discharged for various reasons.

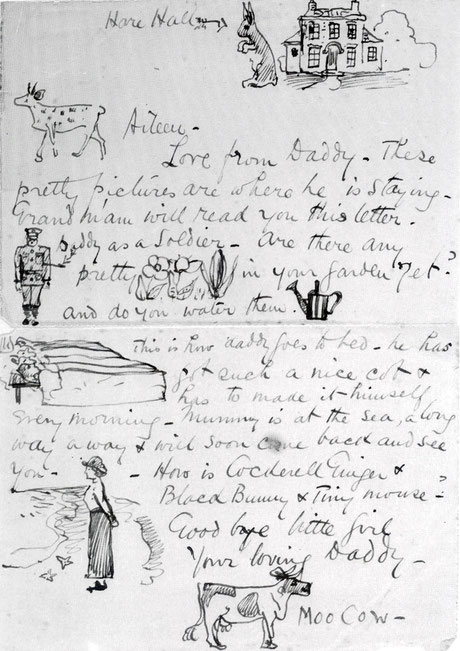

In the spring of 1915, Frank Heath, then aged 42, and living at 'Menwinnion', Lamorna, enlisted and did his training at Hare Hall at Romford in Essex, from where he wrote a charming letter to his eldest daughter, Aileen, then aged 4, back at Lamorna (see image). He joined the 2nd Sportsman’s Battalion of the Royal Fusiliers but, in August 1915, he was transferred to the 30th Battalion Royal Fusiliers, a reserve battalion and it was while serving with them that he contracted meningitis and was admitted to hospital in London. Upon recovery, his wife, Jessica, travelled up to London to take him home to convalesce. (There is, additionally, a story in the family that he was also gassed while fighting in France in late 1915 / early 1916). Whatever happened, his War Record shows that he was discharged from the Army on 1 April 1916 as “no longer physically fit for war service”. The gassing story may well be correct, for he subsequently suffered severe bouts of depression as a result of his experiences.

Algernon Newton, who lived at ‘Bodriggy’, Lamorna, volunteered and joined the Territorial Force, at Exeter, on 3rd September 1914 as Private, 2405. He was then 34 years old, and had had no prior military service. He appears to have been assigned to D Squadron of the Royal 1st Devon Yeomanry, a mounted infantry regiment initially, but then on 12th February 1915 was commissioned into the Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve with the rank of Sub-Lieutenant. In July, he was transferred to the Training Staff at Blandford as an Assistant Musketry Officer, but his time was bedevilled by illness, including a bout of pneumonia, and he relinquished his commission on 21st May 1916.

Richard Weatherby must have been the first Lamorna associated artist to enlist upon the outbreak of the War, for he was passed fit for service in Exeter on 9th August 1914. Unsurprisingly, given his love of horses, he joined as a trooper and his choice of the Royal 1st Devon Yeomanry will no doubt have been influenced by the fact that William Bolitho, the master of the West Cornwall Foxhounds, was the Commanding Officer. However, in November 1914, possibly aware that the mounted section of Bolitho’s Regiment was under threat, he secured a commission, with the aid of a cousin, the Revd John Kelsall, in the Essex Yeomanry Reserve Regiment as Second Lieutenant. He did his training at Earls Hall, St Osyth and, after seven months of this, joined his Regiment in France on 14th June 1915, where it was billeted at Sercus, having been withdrawn from the front line after severe losses at the Second Battle of Ypres in May. Over the course of Weatherby’s service in France, the Essex Yeomanry worked in close collaboration with the 10th Royal Hussars.

As Crosbie Garstin found with his cavalry regiment, it was soon realised that the new type of warfare, with trenches, barbed wire and vast shell-holes, prevented the cavalry from operating effectively as a fighting force, and so they were employed principally for logistical purposes. A significant amount of time was spent digging trenches first at Neuve Eglise and Elverdinghe, and then at Armentieres. Nevertheless, they managed to find time for some polo.

In late September 1915, Weatherby’s regiment was involved in the Battle of Loos. After being placed on alert at 3.30 a.m. on 25th, they spent the next two days, getting orders to move, sometimes mounted, sometimes dismounted, and then being stood down. Once, they got a few hundred yards from the fighting before they were told that they were not needed. Much of the time it was pouring with rain and they had no means of cooking and little opportunity for sleep. Eventually, at 1 a.m. on 27th, they became the advance guard of the relief force that set out for Loos. Lieut-Col Whitmore, Weatherby’s new C.O., commented, “The road leading to Loos from Vermelle passes over the ridge which formed the front line of the German defences. The aspect of the part of the battlefield in this sector, in the moonlight, was weird indeed, the debris of stubborn resistance, guns out of action, broken limbers, ammunition, many brave British Officers and gallant other ranks lying dead, in some cases still holding their maps or rifles in their hands.”(Lieut-Col Whitmore, The 10th (PWO) Royal Hussars and The Essex Yeomanry during the European War 1914-1918, Colchester, 1920, at p.54-5.) The relief operation was not able to be completed during the dark, and so there were casualties in the early light of dawn, and then the line that Weatherby’s Regiment had been designated to hold to the east of the town, by the slag heap, was subjected to prolonged bombardment. It was a difficult day, with communications with HQ intermittent and no water, as the town’s well was in full view of the German marksmen. The trenches that they were in were only partially dug, and so offered limited protection, but due to the chalk nature of the soil and the slag, it proved very difficult, despite working all through the night, to get them into proper shape and to build suitable firing points and the requisite communication trenches. On 28th, things improved somewhat when the infantry captured the high ground and wood which overlooked the city, but search parties sent around Loos to discover hiding Germans saw many gruesome sights. That night, in torrential rain, the exhausted men of the Essex Yeomanry were relieved. However, the action was eventually called off, the British and Commonwealth forces having lost over 20,000 men. [Denis Garstin was also involved in the Battle of Loos and this is the subject of the longest story, The Diary of a Timid Man, in his posthumously published book The Shilling Soldiers (pp.88-163)]

For much of the next six months, the Essex Yeomanry were billeted at Embry, where they concentrated on further training, particularly in relation to the new Hotchkiss automatic rifle and box respirators. With the infantry suffering mounting losses, cavalrymen now started to be used dismounted on a more regular basis, and so they were also trained in trench warfare. On June 24th 1916, the Essex Yeomanry left Embry and, after a series of night marches, often in torrential rain, arrived at Bonnay, where they spent much of July. Whilst constantly on alert to help in the Battle of the Somme, no role for the cavalry could be found. In September, the Essex Yeomanry moved to billets at Aubin St Vaast and had their headquarters at Plumoison, before moving in December to St Josse.

On April 7th 1917, the Essex Yeomanry moved from the Fressin area towards the front near Arras, where they arrived on the 9th. On 10th April, Weatherby led one of a number of patrols sent to investigate the slopes and spurs north of Monchy le Preux and came under heavy fire, which would probably have resulted in more casualties, if a blinding snowstorm had not enveloped them. That night, bivouacked in the snow, they were subjected to a heavy bombardment, and then at 8 a.m., the next morning, the Essex Yeomanry were ordered into battle as the advance party. Weatherby can have had little doubt that it was going to be a difficult day and that morning, as his Regiment tried to establish a foothold in the town of Monchy Le Preux, he was severely wounded by shell shrapnel, in the wrist of his right arm, with superficial damage to his right leg, above the ankle. In all, in the fierce fighting that lasted two days and which did result in the town’s capture, thirteen of his fellow officers were injured, whilst there were 122 men from his Regiment killed, wounded or missing.

As a result of his injuries, Weatherby was sent home on 16th April. His wrist injury proved difficult to correct and despite spells in and out of a number of military hospitals, it was ultimately determined that he was no longer fit for action and he resigned his commission on 8th January 1918. For much of 1918 and 1919, Weatherby, who was said to be “badly affected by the War”, recuperated in Lamorna.

The supreme sacrifice of Benjamin Eastlake Leader (1877-1916)

Despite the fact that he was over-age and his wife, Bell, had just given birth to their first child on 7th June 1914, Benjamin Eastlake Leader, who lived at the newly-built 'Rosemerrin' Lamorna and who was the son of the Royal Academician, Benjamin Williams Leader, and a fine landscape painter in his own right, felt duty-bound to enlist. He was commissioned into The Queens (Royal West Surrey) Regiment and trained with the 3rd Battalion in England. In May 1915, he was posted to the 2nd Battalion, The Duke of Wellington’s Regiment, who were then serving in the Ypres sector of the British Front in Belgium. This Battalion had just been involved in bitter fighting for Hill 60 and only 5 officers and 150 men, from the original 1000, had survived. The battalion remained in the Ypres sector until July 1915, when it moved south to the Somme area in France. Spells of leave resulted in a second child, Alison Mary, being born on 1st June 1916, and photographs in the family album show that he was able to see her, whilst on leave, at his parents’ home, ‘Burrows Cross’. He also managed to get up to Glasgow with Bell and the children to visit Bell’s parents. Like Bell, Bengy’s parents had had to accept that he had been enthusiastic in his decision to do the honourable thing, but this did not prevent them from worrying, and his father was particularly concerned that a tall man, such as Bengy, would have difficulty in the trenches.

It seems clear that there were aspects of war-life that Bengy enjoyed and he was proud of getting his company into excellent shape. However, his last letter to his mother indicated that the trenches where they were “are pretty rotten with no dugouts and we have to put up what shelter we can with water-proof sheets and sheets of corrugated tin; there are not many of these last to be had just here”. However, his artistic eye had been very taken with the sight of a “swarm” of aeroplanes that had come over on the previous day, which had been a gloriously sunny one. “They looked so beautiful - like coloured moths - grey, white, gold as the light struck them”. He then described how he had gone up once in a monoplane and found his first flight a wonderful experience, albeit there was “a terrific rush of air that makes it quite difficult to breathe”. He was also fascinated by the novel perspectives from the air.

Bengy was killed on 12th October at Le Transloy in one of the later actions of the protracted Battle of the Somme. Bell received a letter of commiseration from Major Burke, who had become a good friend. He said that, when they had moved up to the front line, Bengy had been “very impressed with the scene of our troops marching through the French and said it was the only thing he had seen for some time that he wanted to paint.” He indicated that Bengy had led his company magnificently, that they had taken the first German line, but, when advancing to the second line, Bengy was hit and died instantly. He indicated that he was buried “within our lines on the position he gave his life to gain”. How much of this was said purely by way of comfort is uncertain, but seven out of the ten officers involved in that assault were killed, and, in the ranks, 333 were killed, wounded or missing, whilst the survivors of the Battalion were withdrawn to the village of Flers. Clearly, though, these comments did provide some comfort to Bell, as she repeated them to a sympathiser. Very poignantly, she added, “We both knew when he joined that we had this possibility to face, and he did it so cheerfully and gladly that I feel that I mustn’t let sorrow weigh me down. We have always felt that death couldn’t really part us, and I don’t feel now that he is far from me.” One of her saddest thoughts was that “his children will never remember him”.

When Bengy's father died in 1923, Stanhope Forbes made mention of the pride that he had had in his son and commented that "the memory of this brave and gallant young English gentleman... is treasured and deeply revered by all who were privileged to count him as a friend and comrade.”

Submarine Commander artist wins D.S.O. and suffers court martial

Commander George Fagan Bradshaw (1887-1960) settled in St Ives after WWI and was an integral figure in the colony up to his death in 1960. He was born in Belfast and endured an unhappy childhood, as his father, an estate manager, was an alcoholic. At the age of fourteen, he joined the Naval training ship, H.M.S. Britannia, at Dartmouth, and, at the completion of his training in 1909, he enrolled in the fledgling submarine service, purely because it paid more, as he wanted to help his mother and siblings. During his leisure hours, he enjoyed sketching, and he took the opportunity, whilst based in Malta in 1912-3, to take lessons from Edward Caruana Dingli, a local artist of some renown. On the outbreak of War, Bradshaw had been in command of his first submarine - C-7 - since February that year. With limited armament and underwater capabilities, it could only perform home defence duties. However, in August 1916, he was given command of a new boat - G-13, which was faster, had a much greater range and was significantly better armed. His friends rated his chances of survival as pretty slim, as, due to the large death toll, the submarine service was now known as ‘the Suicide Club’, whilst boats numbered -13 were notoriously unlucky.

In early 1917, Bradshaw, who was then based in the River Tees, was detailed to patrol the waters between Scotland and Norway on the look out for U-boats and, on 10th March, he managed to torpedo UC-43 near Muckle Flugga Light, an action for which he was awarded a D.S.O.. Bradshaw also contended that he had sunk a much bigger scalp - no less than the large mercantile submarine the Bremen, the sister ship of the famous Deutschland, which, in July 1917, managed to cross the Atlantic. However, Bradshaw, to his intense annoyance, could not get official confirmation of his achievement, and the fate of the Bremen is recorded as unknown.

Whilst, at one juncture, being hailed as “an exceptional officer of the highest ability”, Bradshaw’s days in the Navy ended in 1921 with a messy Court Martial, after the loss of his second submarine. In November 1918 - just a few days after the end of hostilities - the submarine that he commanded at the time - G-11 - ran aground near Howick, and two men were drowned. Whilst the blame was placed on faulty equipment, not on Bradshaw, the loss of two of his crew at such a time was hard to take. The second loss, which occurred when his new submarine K-15 sank, through a design fault, whilst in dock, could hardly have been Bradshaw’s fault, particularly as he was not present, but nevertheless the powers that be insisted on a Court Martial. Whilst acquitted, the authorities, having no doubt been privy to some choice words from Bradshaw, decided that he should not again be placed in charge of a submarine. Whilst furious at the indignity of his exit from the Navy, he later admitted that his nerves had been shot through.

During his time in the Service, Bradshaw developed a good reputation amongst his fellow officers as an artist, albeit he was still, in truth, an amateur, and he received commissions to paint a number of their submarines. The Royal Navy Submarine Museum at Gosport now own a large number of these works, depicting submarines of each of the C-, D-, E-, J- and L- classes. Several of these were made into postcards. By far the most assured work is a large oil, On Patrol 1914-1918. Another interesting oil is U-boat sinking barque by gunfire, an event Bradshaw will surely have witnessed through his periscope. After settling in St Ives, Bradshaw occasionally returned to wartime subjects, which he exhibited on Show Day and elsewhere. Indeed, his exhibits on his very first Show Day in 1922 included A Broadside from a Super-Dreadnought. Even as late as 1937, his Royal Academy exhibit of the year, Surface Patrol, featured a submarine.

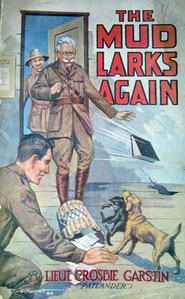

Crosbie Garstin ('Patlander') and The Mud Larks

Garstin had a number of poems and comic stories published by Punch during 1916, but the first piece using the title The Mud Larks appeared in the Punch issue of 7th February 1917. This was the one that became known in the first compilation as The Messless Mess, albeit none had sub-titles when first published. It was only on the publication of the fourth Mud Larks story, on 23rd May 1917, that Crosbie adopted the nom-de-plume ‘Patlander’, which he used for all his future Punch contributions, whether poems or short stories. It is possible that his continuing service at the Front necessitated the use of a pseudonym, but it is informative that he should use the term ‘Patlander’, a slang term for an Irishman. Garstin was proud of his Irish heritage, but also keen to imply that he pedalled an Irish sense of humour.

The Mud Larks series became enormously popular, and compilations were produced in 1918 and 1919, and he continued to produce them until June 1919, albeit none of the 1919 articles are included in the second compilation and so are completely unknown. His contributions to Punch ended in 1922.

Extract from the first Mud Larks story, The Messless Mess

“Our mess was situated on the crest of a ridge, and enjoyed an uninterrupted view of rolling leagues of mud; it had the appearance of a packing-case floating on an ocean of ooze. We and our servants, and our rats and our cockroaches, and our other bosom-companions slept in tents pitched round and about the mess.

The whole camp was connected with the outer world by a pathway of ammunition boxes, laid stepping-stonewise; we went to and fro, leaping from box to box as leaps the chamois from Alp to Alp. Should you miss your leap, there would be a swirl of mud, a gulping noise, and that was the end of you; your sorrowing comrades shed a little chloride of lime over the spot where you were last seen, posted you as ‘Believed missing’ and indented for another Second Lieutenant (or Field-Marshal, as the case might be).

Our mess was constructed of loosely piled shell boxes, and roofed by a tin lid. We stole the ingredients box by box, and erected the house with our own fair hands, so we loved it with parental love; but it had its drawbacks. Whenever the field guns in our neighbourhood did any business, the tin lid rattled madly and the shell boxes jostled each other all over the place. It was quite possible to leave our mess at peep o’day severely Gothic in design, and return at dewy eve to find it rakishly Rococo.

William, our Transport Officer and Mess President, was everlastingly piping all hands on deck at unseemly hours to save the home and push it back into shape; we were householders in the fullest sense of the term.”

Having worked out that it was the heavy guns of their own side, who caused the most vibration, they had just got that detachment to move, when a mule ran free in the night and demolished the whole structure.

Extract from the second Mud Larks story, The Ferts

Crosbie joined an old school friend of his, Freddy, in his dug-out, which was the Officers’ Mess, which he described as “a nice hole, cramped and damp, but very deep, and with those Bosche love-tokens thudding away upstairs I felt that the nearer Australia the better”. However, the company was not to his liking.

“Never before have I seen rats in such quantities; they flowed unchidden all over the dug-out, rummaged in the cupboards, played kiss-in-the-ring in the shadows, and sang and bawled behind the old oak panelling until you could barely hear yourself shout. I am fond of animals, but I do not like having to share my tea with a bald-headed rodent who gets noisy in his cups, or having a brace of high-spirited youngsters wrestle out the championship of the district on my bread-and-butter.”

Freddy, having woken up one morning to find a rat sitting on his face combing his whiskers instead of its own, had sent home for a pair of ferrets. These had done sterling work for a few days, but had then taken up residence in the next dug-out, occupied by ordinary soldiers. Garstin commented,

“It is the nature of the British Atkins to make a pet of anything, from a toad to a sucking-pig - he cannot help it....[The ferrets] were taught to sit up and beg, and lie down and die, to turn handsprings and play the mouth organ; they were gorged with Maconochie, plum jam and rum ration; it was doubtful if they ever went to bed sober. Times out of number they were borne back to the Officers’ Mess and exhorted to do their bit, but they returned immediately to their friends the Atkinses, via their private route, not unnaturally preferring a life of continuous carousal and vaudeville among the flesh-pots, to sapping and mining down wet rat holes.”

Cecily Sidgwick - A German origin novelist in Lamorna

The media frenzy about the enemy within during the War will not have made life very comfortable for Lamorna resident author, Cecily Sidgwick, who not only had German parents, but also had gained a reputation as an expert on Germany as a result of both her fiction and non-fiction books. In 1908, she had published Home Life in Germany, an account, principally, of the role of women in German society, whilst, the following year, she had produced a children’s book on Germany, in the Peeps at Many Lands series. In addition, the vast majority of her romantic novels contained German settings and German characters, so that she could contrast and compare the attitudes of the English and the Germans to such matters as education, childcare, courtship, marriage and the running of the family home. Whilst such comparisons often resulted in some gentle mockery of German traits and attitudes, she was nevertheless inextricably linked in the eyes of her public with Germany.

Whilst her friends in Lamorna will have not given her German connections a second thought, it will not have taken too much tittle-tattle for less well-educated locals to develop extraordinary suspicions given known instances of the paranoia that did develop in the locality - N.B. the case of Rolf Jonssen above.

The outbreak of hostilities with Germany will not have come as a great surprise to the Sidgwicks due to the attitudes towards England that they had experienced during their visits to that country earlier in the century. Alfred Sidgwick, talking to The Daily Mail in 1917, commented, “When you were in Germany, people talked to you about England morning, noon and night; chiefly, about its hypocrisy, decadence and greed. You said, ‘England, my England’ to yourself, smiled blandly and listened to distorted history in amazement, wondering whether your encyclopedic host believed what he told you or was letting off spleen. Others talked of English manners, of English education and of English literature. Our manners were arrogant, we had no education and we had no literature. Here and there you met someone who knew us and liked us, and that made a pleasant change. But everyone had England on their nerves.” As early as 1901, Cecily’s novels contain German characters who desired England to be “annihilated”, largely due to their biased interpretation of English conduct during the Boer War, and even a well-rounded German character in The Lantern Bearers (1910) could not understand his country’s delay in seizing a wealthy and, by their own reckoning, a defenceless land. ‘One army corps would be enough,’ he often observed. ‘I have often conducted the whole operation with my uncle, the Major. It is as simple as flying.’ ” (1915 Ed. p.68-9).

Such comments would have drawn a laugh at the time amongst her English readership, but the reality was now rather frightening. Accordingly, at a professional level, how should Cecily adjust? Should she ignore Germans and German settings altogether as being uncommercial subjects, or should she populate her novels with Germans displaying the very worst of their nation’s characteristics and lampoon them?

Initially, in Mr. Broom and his Brother (1915), she departed completely from her past practice and set the novel in an imaginary country, Katavia, which had characteristics not unlike Zenda, but nevertheless the War and cruel Germans did feature. It does not appear to have been a success, though, as few copies survive, and so she resorted to reverting to German settings but making her German characters display all the characteristics that the British media disparaged the most. Salt and Savour (1916), for instance, was set in the immediate pre-War period and was about an Englishwoman, Brenda, who had married into a German family. At this time, she commented that there was throughout Germany a malevolence towards England and a desire to punish the English for perceived wrongdoings. The book captured the mood of the time perfectly. The Aberdeen Daily Press stated, “We question if Mrs Alfred Sidgwick has written anything that has struck the hour with a vibration like this novel”, whilst the Sussex Daily News hailed it as “the greatest novel which the war has up to now called forth”. The Pall Mall Gazette went further, “We like this book so much that we should be glad if everyone could read it to get a clear idea of what we are fighting about....Mrs Sidgwick’s pen has performed a great national service.”

The book was published in America, in 1917, under the title Salt of the Earth, a phrase used by the Kaiser in his famous speech at Potsdam, where he had said, “We are the Salt of the Earth. God has chosen us to regenerate the world. We are the apostles of Progress.” The book was an enormous success there, consistently heading the lists of best selling novels for months. Having made a breakthrough in that market, Cecily ensured that, in her next novel of this type, Karen, one of the principal figures was an American, who was a consular figure in Germany before joining up when America itself entered the War. Again, it featured the English bride of a German, and contained even more venemous German characters - men who committed war crimes in Belgium and boasted of living in English country houses and of imposing indemnities that would bleed England dry, women who treated prisoners of war with barbarity, and children who were bullied and ill-treated by their elders and who committed suicide when they failed their examinations. Herbert Thomas’ increasingly jingo-istic reviews of her books of this period in The Cornishman do not make comfortable reading, but they were very difficult times.

Due to the international success of Salt and Savour, Cecily seems to have received larger payments for Karen, (which was renamed for the American market, The Devil’s Cradle), than any of her other books, possibly as an inducement to change publishers from Methuen to Collins. Indeed, it was the largest earner for her, in terms of book royalties, of her career.

Cecily did break away from her anti-German obsession for one novel, Anne Lulworth (1917), which was set in wartime Cornwall. This highlights a number of the petty disputes that arose, as to how best to help the war effort, and also features a conscientious objector. The novel is set before conscription was introduced, but, nevertheless, the man’s views are dismissed as inappropriate in the circumstances and he is widely held in contempt. Whilst the adults nevertheless outwardly behaved with decency towards him, the children plagued him by pressing upon him white feathers.

Cecily’s first book after the War, The Purple Jar (1919), was another novel full of venemous Germans. Thereafter, though, albeit she did not abandon German characters altogether, she reverted to her normal much gentler form of humour. However, Cecily clearly knew her market, and she was able to exploit what could have been a very difficult scenario during the War years to secure her greatest commercial triumphs, even if these books lack the subtlety of her best works.

Crosbie Garstin's front line action during 1917

After his spell in Ireland, Crosbie Garstin rejoined his regiment, King Edward’s Horse, in France in December 1916 and found the conditions there dreadful - just a sea of ooze. The trenches were blown in and flooded out and one waded about in mud up to your knees. It was, he said, “like living in a sewer which is being blown up”.

In March 1917, Crosbie experienced serious front-line action for the first time at Rosieres, when the Germans began their strategic withdrawal to the Hindenburg LIne. In a letter dated 30th March, Crosbie told his parents,

“On St Pat’s morning (17th March), we were miles behind the lines doing a field day - in the afternoon we were being rushed forward to the real thing.... We went over the top & on & on & on, till we bumped hard against the Bosche, and there we remained holding a line of sorts with a few scattered forts, while the army crawled very slowly up behind us....Away out in the blue, on our own in the open, tight up against the Bosche in strength, covering the advance for the British army, is inspiriting work, but nervy and very wearing - 48 hours on end was nothing.”

Later, he indicated that they had been some thirty miles ahead of the infantry and the artillery, without any communications to speak of, and that they had been heavily outnumbered by the German horse. He commented, “One went out on patrol without much hope of coming back”. It was just after having been ordered into “one particularly nasty stunt” that some copies of his first book, Vagabond Verses, arrived. “I pushed one copy into my saddle wallets, and rode into action cheerfully, crooning a sort of ‘Nunc Dimittis’ to myself - I had seen my first book.”

Having ridden into one liberated town, which the Germans had set on fire, he recorded how the civilians, albeit weak from starvation, had already hung from the remaining houses in the square tricolours that they had secreted away, and cheered like mad. It was a memorable and touching scene.

“A girl kissed me brazenly before my troopers, everybody shook hands and laughed and cried. Vive la France - Vive l’Angleterre - all was well with the world once more. My chestnut charger, ‘Dick’, (a showy little fellow) was patted and fondled, two girls took his bridle and marched him up and down tenderly as he were a sort of a sacred thing. They pressed all about me letting loose the pent-up excitement and interest of two and a half years - the smoke of the burning town sweeping about all the time.”

Crosbie was incensed by the wanton destruction that “the Bosche” had indulged in as they retreated. “He has leveled villages, blown up, smashed, battered, burnt and ruined every blessed thing with a diabolical thoroughness. In some places where he hadn’t time to finish the job, he ran about with a hammer scarring everything. I’ve seen rooms where he’d dragged the wall paper down and trampled all over the ornaments, bashed in the panels of a side-board etc.” One of his enduring, horrific memories was finding a live kitten nailed to a door in Étreillers. Eventually, after ten days, the infantry caught up with them and they were relieved in a snow-storm - “About dead-beat and all in too.”

In early June, the regiment marched through the desolate landscape of the Somme battlefield to Le Sars. Crosbie told his parents, “The country is a desert for miles around. What few trees are left are just charred and shattered stumps, whole villages just heaps of matchwood and brick dust - for the rest its just shell-holes, debris, rotting corpses and smells of chloride of lime and dead tanks....I was on observation here last winter and the whole place was black with bursting shrapnel and brown with mud spouts - now a sort of death calm hangs over the place.”

In late July 1917, Crosbie’s Squadron took part in the Battle of Passchendaele, being given a reconnaisance role, immediately following the initial tank assault. However, they soon experienced raking cross-fire on terrain that was not suitable for horses, and, in a very short timescale, nearly fifty percent of the horses were hit, casualties amongst the troops being less severe, as the fire had been aimed low. Having dismounted, the survivors ended up in shell holes by the Steenbeck river, where they stayed all night, as the Brigade’s front line. Crosbie told his mother, “It was very unpleasant lying out all night in a shell-hole soaked to the bone, plastered in mud, the water creeping up your legs, the High Explosive cracking all around and the machine gun bullets whining overhead - its enough to drive a fellow grey-headed.”

After this traumatic experience, which demonstrated that cavalry was totally unsuited for modern warfare, Crosbie received some leave and met up with his parents, who were in Chipping Campden, with a party of art students. His mother, Dochie, told his sister, Alethea, “Cob looks older and greyer and I see a pathetic ‘beyond’ look in his eyes, which hurts me.” Nevertheless, he was “perfectly sweet and loving” towards her, and told amusing, and often rather risqué, stories to the female students. However, when he departed, she recorded, “Dear Old Cob has just left, and - well - bereft was not the word for it - blank and dead we felt.”

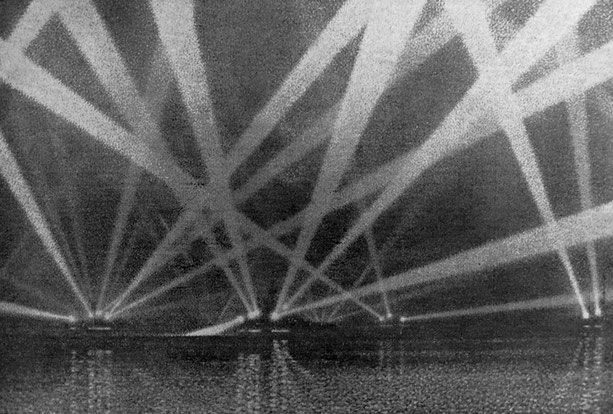

During the stalemate in the mud that followed Passchendaele, Crosbie was sent off on detachment to a pretty lively spot, with an observation balloon in the back garden, an ammunition column on either flank, and an infantry battalion camped in front.22 Every night, they got bombed.

“Promptly after Mess, the song of the bomb-bird is heard. The searchlights stab and slash about the sky like tin swords in a stage duel; presently they pick up the bomb-bird - a glittering flake of tinsel - and the racket begins. Archibalds pop, machine guns chatter, rifles crack, and here and there some optimistic sportsman browns the Milky Way with a revolver.”

Accordingly, Crosbie was immensely relieved when he was pulled out in early November. He confided to his mother, “I had been under constant shell and bomb fire for three months and the complete quiet here is most uncanny. I had a n’awful amount of luck where I was; one morning a bomb killed sixteen men alongside my camp and eight were splashed out by a shell the next day. It went on night and day and I never got a man or horse scratched. On one occasion a large lump of shell knocked my washstand out of my hands which was near enough.”

Crosbie’s period of quiet was brief, for, in late November, the regiment also took part in the Battle of Cambrai. Crosbie’s Squadron went ‘over’ early on the first day, and they “got caught in a barrage and cuffed this way and that for fifteen infernal minutes, amongst other things.” However, he was disinclined to go into much detail. “It’s war you know and never very funny at any time. These big pushes don’t amuse me any - some of the sights one sees are bloody horrible.”

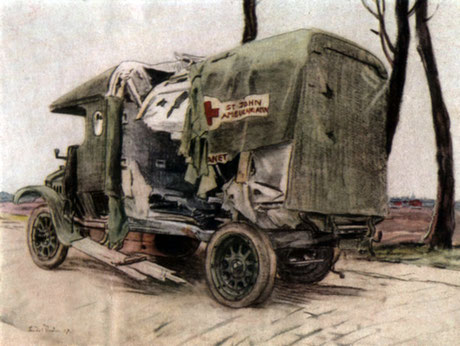

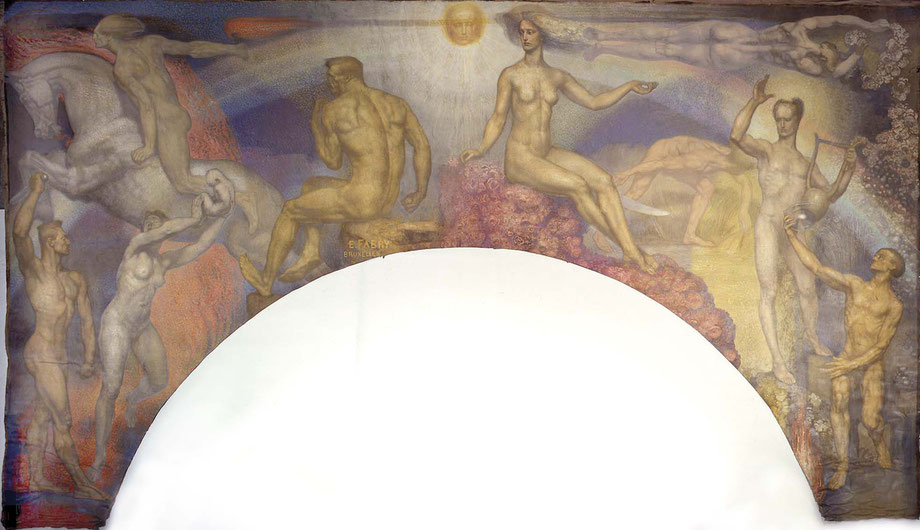

Ernest Procter and the Friends Ambulance Unit

The Newlyn artist, Ernest Procter, was a conscientious objector, but in April 1916 he joined the Quaker organisation, the Friends' Ambulance Unit. After a short training period at Jordan's, Bucks, he arrived in Dunkirk in June 1916. In September, he was appointed as an offical artist at the Works Dept and until February 1919, produced numerous sketches of the operations of the Unit. Some 200 of these are held by the Imperial War Museum. When a History of the Friends Ambulance Unit was produced in 1919, the majority of the illustrations were by Procter.

His sketches cover a wide range of subjects. For instance, there are a number of Queen Alexandra Hospital at Malo, showing the various wards, the kitchen, the dug out and damage caused by shell fire etc. There are also several showing 'Poste de Secours', with red crosses painted conspicuously on their roofs/walls in the hope of escaping bombardment. IWM also have a series of a garage at Boulogne,where much needed work was done to keep the ambulances in service given the state of the roads they had to cope with. After the end of the War, Procter did sketches of the devastation at places like Ypres and Peronne.

In 1980, there was an exhibition of over a hundred of Procter's war drawings at Blond Fine Art, from which this work was acquired for the Government Art Collection. It is inscribed on the back “Albert / Switch line to the Bapaume Rd. / Showing the Broken Bridge in the floods / due to the smashing of the Canal Banks.”

The image below of the moat at Ypres was the front cover illustration of the catalogue.

Despite the mass of material produced by Procter, I am not aware of any exhibition or analysis of this having been done to mark the centenary of its production.

See also the work held by the descendants of Molly Evans, who worked alongside Procter at Queen Alexandra Hospital, Malo.

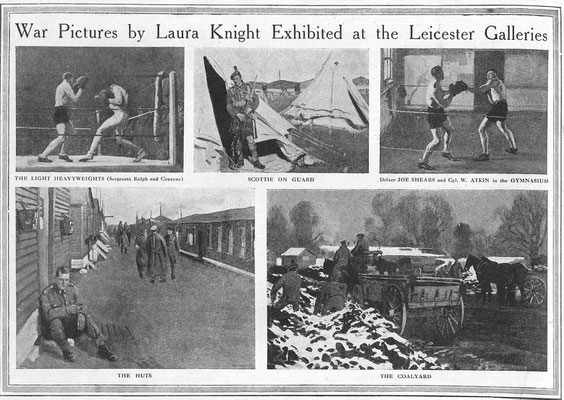

Laura Knight’s depictions of the Canadians at Witley Camp, Surrey

In February 1918, Laura Knight held an exhibition at Leicester Galleries entitled Camp Life and Other Pictures, which showcased the series of paintings of the Canadian armed forces at Witley Camp, Surrey that she did in the autumn of 1917. Laura wrote at length in her autobiography, Oil Paint and Grease Paint, about this commission from the Canadian Government that she received, through P.G.Konody. She indicated that the original idea had been for a painting depicting the men swimming nude in a river, but that when she got there in November 1917, there was no river anywhere near and there was snow on the ground, so that outdoor subjects were not particularly appealing. Her initial impression of the camp was it was dull and ugly - “row after row of brown huts and khaki-clad figures drearily standing about in the mud”. However, she then came across Joe Shears, a boxer “with a cauliflower ear, a half-closed eye and a beetling brow”, who was the bantam-weight champion of all the forces, who became her “devoted attendant, model, teacher of all points of the sport”. The gymnasium, therefore, became her studio, and her principal painting, which was acquired for the Canadian War Museum, was a depiction of Joe, wearing black satin trunks and a red sash - “a beautiful, glorious colour scheme” - in a bout with another of her regular models, Corporal W. Atkin. However, she decided to transfer the contest from the gymnasium into an open air landscape setting with crowds of spectators, and did so remarkably successfully.

In the February 1918 exhibition at the Leicester Galleries - her first solo show - , there were nine ‘camp life’ subjects included amongst the twenty seven exhibits. Five of these were illustrated in the above illustration in The Graphic - The Light Heavyweights (Sergeants Rolph and Cocayne), Scottie on Guard, Driver Joe Shears and Corporal W.Atkin in the gymnasium, The Huts and The Coalyard. Timothy Wilcox, who wrote an article on this exhibition in The Burlington Magazine in September 2015, also located an image of General Service Waggons Coaling in a magazine, The Queen (23/2/1918) and of Driver Joe Shears punching the ball in Country Life (23/2/1918), albeit the latter was for some reason not included in the exhibition. The other ‘camp life’ titles were The Forage Barn, The Riding School and The 60-pounders. Somewhat surprisingly, the current whereabouts of all these other paintings (and of the mass of preparatory sketches that Laura did) are not known.

Alfred Munnings with the Canadians in France, 1918

(research by Bill Teatheredge of the Munnings Museum)

Alfred Munnings had been determined to enlist, but was rejected firstly for being too old and then because he was blind in one eye after a hunting accident. However, in 1917, he became a strapper doing the most menial jobs at a Remount Centre near Reading before gaining a commission from Max Beaverbrook, who wanted the Canadian war effort immortalised in art.

In early 1918, Munnings joined up with General Seely and the Canadian Cavalry Brigade in France. On the first day, Munnings began painting General Seely on the great war horse, ‘Warrior’, in sight of the German gun positions and with ‘Warrior’ gradually sinking in the mud. It is now one of Munnings' most acclaimed paintings. Munnings was immediately accepted by General Seely, who commented, ‘Of course it had never been the intention of the Canadian authorities that Munnings should join us in the front line, but this whimsical and gallant soul thought that this was just the best place in which to be.’

With the Brigade at rest behind the lines, Munnings used the troops of men and horses as readily available models. With an officer, Captain Torrance, available to marshal everything, Munnings would stage a variety of scenes. Many of these were simply the troopers going about their everyday business, such as watering the horses, or riding off as if they were ‘on the march.’ Munnings did a variety of sketches in sketch books, then worked up some of those into studies before doing final versions in oils on canvas, which he tended to hang up to dry in the Officer's Mess.

The brigade was then ordered to move off through the Somme region, where he observed the destruction that towns such as Peronne and Cambrai had suffered. It then got caught up in the German Spring Offensive, during which it was forced to retreat. Munnings, therefore, experienced the full scale German bombardment and some testing times, sleeping in lofts and in woods, during a fairly chaotic retreat. With his store of paintings, he had become a liability, but although ordered home, he met up with two colonels from the Canadian Forestry Corps, who persuaded him to depict their activities. Accordingly, he stayed on to paint the lumberjacks and their teams of horses as they provided wood for the war effort in The Forest of Conche, Normandy. Moving on to the forest of Dreux, Munnings wrote, ‘These lumbermen were grand fellows. Their speech, dress, cast of countenance and expression belonged to the illimitable forests of Canada.’ His last call was the Jura region, where he continued painting until he received further orders to return home.

Exhibited in 1919, Munnings’ 45 paintings of the Canadian Cavalry Brigade and Forestry Corps were shown first at Burlington House, London, then New York, Montreal and Toronto, introducing his work to an international audience. Munnings considered his experiences among the most rewarding of his life and he remained a lifelong friend of General Seely. His portrait of the General has just been re-created with Brough Scott, the General's grandson acting as model, and his war paintings have been gathered together for the first time since 1919 in an exhibition at the National Army Museum, London, which runs until 3rd March 2019.

Harold Knight - Pacifist

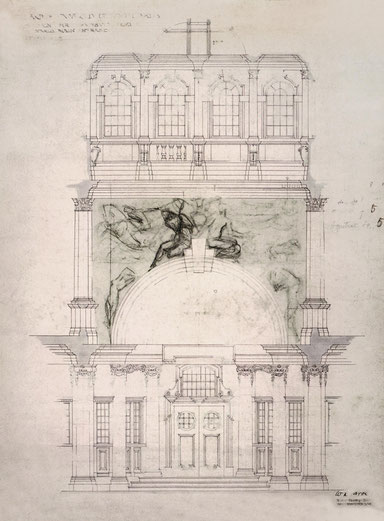

Harold Knight, who had always studied politics deeply, “passionately believed that pacification between nations could be settled by talks round a table rather than in the fighting line”. He also "believed a human being was the highest manifestation of God on earth and to destroy even a body of a human being was to destroy a part of God." Accordingly, he believed killing man would be wrong to do as an individual and equally wrong in obedience to an order from the Government.