Cecily Sidgwick biography - Chapter 8 - The Lamorna Art Colony

1912 was a transformational year for the Lamorna art colony, as a number of new houses were built that year in the valley as homes for artists, whilst the Sidgwicks too decided that they enjoyed Lamorna and its community so much that they would settle there permanently and build themselves a new home.

All this development was only possible because Colonel Paynter, who owned one side of the valley, was prepared to sell off land to enable the new properties to be built. Rather eccentric in his likes and dislikes, he somewhat surprisingly rather took to the artistic fraternity, who provided a little local colour. His local land agent, Gilbert Evans, who had started work for the Colonel in 1909, was well-liked in the community, and was able to resolve any areas of disagreement with the minimum of fuss. He also soon became an integral figure in the social life of the artists as well.

The Sidgwicks’ decision to become property owners will have been sparked by the transformation in Cecily’s earning capacity in the previous couple of years. The success of The Kinsman and The Severins meant that she had been able to command an advance of £278 for her 1911 novel, Anthea’s Guest, and of £315 for her 1912 novel, Lamorna, whilst her earlier works were being reprinted as well. Her total income in 1911 was £456, as compared to 1909’s £176. Their new house, ‘Trewoofe Orchard’, was a four bedroom stone-built property, in four acres, and it was to be their home for the rest of their lives. This was right at the top of the Lamorna Valley, in the Parish of St Buryan, and was only a short walk across the common from their previous home, ‘Vellensagia’.

As already mentioned, Harold and Laura Knight soon became close neighbours, when they moved in to the renovated major section of ‘Oakhill’. Not content with having put them up for some time while the cottage was finished, Cecily gave them some house-warming presents as well, as Laura recorded in her autobiography. "Mrs Alfred Sidgwick gave us a handsome bow-fronted mahogany chest of drawers as a house-warming present, which we still have, and the big blanket she gave us is on my bed at the present time." It is rather interesting that these gifts had stood the test of time, as Laura rather shocked her neighbours by her extravagance in ordering all her other furniture, linen and silver from Harrod’s catalogue. The Knights’ home soon became a focal point in the social life of the community. Laura commented, "At Oakhill, we kept open house as we had always done; almost every evening people gathered round our fire. The gramophone was constantly playing for dancing on the rush matting that covered the stone floor."

The taller cottage in the run (now known as ‘Oakhill Cottage’) was occupied by Mrs Eunice Shaw, the mother of art students, Gerard Shaw and Dod Shaw (later Procter), and it seems likely that Cecily knew them and its interior layout quite well, as she used it as the home for the principal characters in her novel, In Other Days. Dod Shaw was then one of the leading students at the Forbes School, but none of Cecily’s characters seem to bear much resemblance to her. John Birch, for one, was not over-fond of Dod, thinking her unnecessarily argumentative. Alfred Munnings was also around. He had paid a number of visits to Newlyn for some years, lodging, on occasion, with the Knights, during which time he was more renowned as a party animal than a painter. However, he had started to base himself more in Lamorna after 1911, and this had led to his ill-fated courtship of art student, Florence Carter-Wood, whom he married in January 1912. He is unlikely to be a person with whom the Sidgwicks bonded closely, but he could not be ignored, and they were guests at the famous Sausage Supper, organised by Munnings, which was held at Jory’s on 6th April 1912. The event was a way of thanking Gilbert Evans, after he had realised that the proposed evening barbeque in the woods held the day before (Good Friday) lacked one essential ingredient - namely sausages - and had cycled off to Penzance to acquire some off a rather disgruntled butcher, who did not appreciate being disturbed out of hours on a Bank Holiday. Cecily had the honour of being placed on the right hand of the principal guest, Gilbert Evans, whilst Alfred Sidgwick was to the left of Munnings’ wife, Florence. Dick and Peter Ullmann were present, but not their parents, the two boys being in the midst of their normal Easter holiday break with the Sidgwicks. Others present, in addition to Munnings himself, were John and Houghton Birch, Arthur Tanner, an early resident of the Valley, who was recorded as living at ‘Vellensagia’ at the time of the 1901 Census, Harold and Laura Knight, Thomas and Caroline Gotch, Benjamin and Isabella Leader, Mrs Shaw, Gerard and Dod Shaw, Denis and Crosbie Garstin (the latter back briefly from his adventures in Canada), Lionel Evans (brother of Gilbert), Dolly Snell, a ballet dancer who had become a model and friend of the Knights, and someone whose surname was Hogg. With Munnings on ebullient form, it was an evening that lived long in the memory of all who attended, and helped to dull the blow dealt by the recent death and funeral of Elizabeth Forbes.

Cecily also knew and was friendly with Norman Garstin and his family, for her album contains a series of lithographic Christmas cards from him featuring Breton scenes - Josselin (1911), Guéméne (1912) and Le Faouet (1913). As both his sons, Dennis and Crosbie, had aspirations to be writers, they will have been interested in Cecily’s knowledge of the literary world, whilst she will have been keen to foster their talent.

Of the other guests, it was the Leaders, with whom the Sidgwicks got on best, particularly as they became close neighbours. Benjamin Eastlake Leader, who was born in Worcester on 17th June 1877, was the son of the well-known Royal Academician, Benjamin Williams Leader, and, like his father, was interested in landscape painting. He first exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1902, when he was still living with his father at ‘Burrows Close’, near Shere, in Surrey, but appears to have studied at the Forbes School on and off during the rest of the decade, as he sold a work from the Newlyn Art Gallery in 1904 and exhibited at the Royal Academy Cornish Moorland in 1906 and Moonlight on Mount’s Bay in 1910. It was on 8th September 1910 that he married Isabella Anderson in Glasgow and the pair decided to settle in Lamorna, living first at ‘Oakhill’ (1911-2), then ‘The Reens’ (1913), before having ‘Rosemerrin’ built in 1914. The Leaders were both good-looking, very personable and much in love. Indeed, Lamorna Birch told his wife that he felt rather jealous of their obvious passion for each other, when he accompanied them on a painting trip to Switzerland in January 1912. One of the photographs in Cecily’s album is of a young artist cleaning a large landscape featuring a line of trees and my best guess is that this will be of Benjie Leader and his 1914 Academy exhibit Hedgerow Elms.

‘Rosemerrin’ was a large house, constructed of local granite and built in the style of a Cornish manor, with low-beamed ceilings and pitch pine timbers. It also included a large, well-lit studio, which is still a most impressive space. Whilst the access drive to it, which was shared with that of the Hughes’ house, ‘Chyangweal’, was some distance away along the road to Boleigh, one boundary of the property adjoined that of the Sidgwicks’ home, ‘Trewoofe Orchard’, so that there was no distance at all between the two houses, albeit an area of woodland screened the two properties from each other. It had in its grounds a Fogou - a rare underground dry-stone structure dating from the Iron Age - which was surrounded by an oval, single-banked ancient fort, whose stone ramparts were still partly in place. However, in days when such ancient remains were not so prized, any interesting remains of the interior of the fort appear to have been destroyed in the construction of the house itself, whilst the fort’s palisades were removed and the stone used for landscaping the garden. Cecily was clearly most impressed with this, as, in her novels, she frequently has Mary Clarendon taking guests across to see the rock garden in her neighbours’ property, and also the Fogou itself, which was not affected. Benjamin Leader seems to have had an interest in botany, as he is recorded as registering with the Botanical Society of the British Isles, jointly with Cecily’s nephew, Dick Ullmann, Lilium pyrenaicum in June 1913, whilst Dick himself registered a Viola found at ‘Rosemerrin’ in July 1914. Benjie’s 1915 Royal Academy exhibit was A Corner of My Garden, whilst a number of other rock garden studies by him have also come on to the market.

Another couple, who settled at the top of the valley in 1912, with whom the Sidgwicks got on well, were the Napers. Ella Naper (b.1886) was a jeweller, who had trained at Camberwell School of Arts and then worked for three years at Branscombe, Devon, under the guidance of Fred Partridge. It was there that she met her future husband, Charles, a painter, who had trained at the Royal Academy Schools, but who came from a distinguished Anglo-Irish family, who were not impressed with his choice of bride, when they married in 1910. They decided to come to Cornwall after their marriage "in search of a way of life which freed them from the conventions of society. They had made a decision to care only about what really mattered to them, the enjoyment of nature, the nurturing of friendships and the creation of beautiful things: a home and garden, jewellery, ceramics and paintings." After some time at Looe, they came to Lamorna, which proved to be ideal, and acquired in 1912 three fields close to ‘Trewoofe Manor’, upon which they built their home ‘Trewoofe House’ to a design by Charles. They too became close friends of the Knights and Ella modelled, often nude, for a number of artists in the valley. Like Cecily at ‘Trewoofe Orchard’, she also enjoyed creating an attractive garden, which had a stream running through it, and this was depicted in a well-known painting by Lamorna Birch.

Others to join the colony in the near future were Frank and Jessica Heath, two artists who had met at the Forbes School, who built, at the cost of £1,000, the grandest of the new properties, a large five-bedroomed house, which they called ‘Menwinnion’, whilst, in 1911, Robert Hughes and his New Zealand wife, Eleanor, built ‘Chyangweal’, close by, on the road to Boleigh. Robert, who had often based himself at the Cliff House Hotel since 1909, had become a good friend of John Birch, sharing an interest in shooting and fishing, and Eleanor, who was a fine musician, was well-liked. Their home was to become a regular haunt on Saturday evenings. In addition, on the road down to the Cove, Algernon Newton, whose family were connected to the artist materials firm, Winsor and Newton, and his wife had built ‘Bodriggy’ in 1912.

In addition to new houses, Colonel Paynter was also happy to give permission to the erection of studios and painting huts. Laura Knight even had one built on the cliff edge close to the rock pools where she often painted both local girls, and models brought down especially from London - the latter causing some controversy by occasionally posing nude. Cecily records the local outrage, in her normal witty manner, in None-Go-By, when Mrs Lomax, of ‘Morwenna’ comments on the artists, "Some of them paint from what they call the nude. They seem to think it doesn’t matter, if they call it that. Brazen hussies! Mr Lomax says it is a case for the police, but he has never taken it up. He went all over the rocks himself several times last year, but only came on landscapes, so he could do nothing." "How unlucky!" said Thomas dreamily."!

The colony was born and, as most shared similar ideals, they developed an idyllic way of life, which combined hard work at their principal passion, which, for some, was painting, for others, gardening, coupled with an enjoyment of both the spectacular cliff scenery and the flower-carpeted woodland of the valley. Then, in times of leisure, there were soothing discussions and debates, which may or may not have hit any great intellectual heights, games of chess and cards, plus a healthy dose of partying. It was a bohemian existence, free from many of the stifling conventions of the day, where financial considerations were of little relevance. The much older Sidgwicks could easily have been seen and treated as two old fogies, who were out of place, but, to the credit of all, they became integral figures in the community, and were referred to fondly as 'Mr and Mrs Sidgie/Sidgy'.

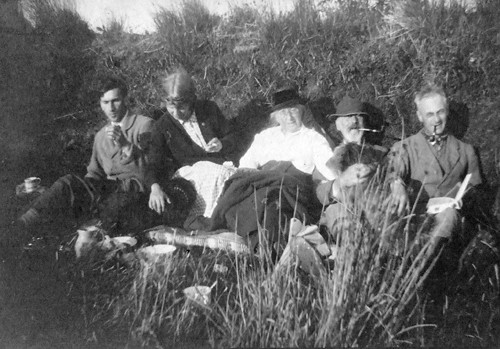

Perhaps one of the best examples of how they fitted in is that they were invited up to the Napers’ hut at Dozmary Pool on Bodmin Moor with the Knights. The holiday that the Napers, the Knights and Harold and Gertrude Harvey spent in gypsy style by the side of this legend-linked lake in August 1914 was immortalised in Laura Knight’s autobiography. She loved the back-to-nature, bohemian lifestyle in this isolated spot, with skinny-dipping in the lake, whilst her customary dedicated painting periods were broken up by long moorland walks. However, she makes no mention at all in her account of the Sidgwicks. Nevertheless, photographs in the Napers’ album indicate that the Knights and the Sidgwicks were there together in 1914, enjoying walks over the moors and picnics. One shows Cecily and Ella on top of Brown Willy, a nearby hill. As the Harveys do not feature in these particular photographs, it is possible that they did not stay the whole time and that, when they left, the Sidgwicks joined, sleeping, like the Harveys had done, in the farm nearby. It proved the last glimpse of the rural idyll, as the guns of war had started by the time that they all arrived back in Lamorna.

David Tovey - Cornish Art Historian

David Tovey - Cornish Art Historian